Monday, December 31, 2018

Professional and Expert Linguists Salute School Language Brokers

Here's some good news to see out 2018.

The Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL) is the UK's most prestigious association of Expert and Professional Translators, Interpreters and Language Teachers. It's the most prestigious for several reasons. For one thing, it's the oldest, having been founded in 1935 by a visionary, Sir Lacon Threlford, who saw the importance of languages for business and government. Second, its examinations and qualifications are internationally recognised. (I was a Fellow of the CIOL myself for many years.) And last but not least, it's constituted by Royal Charter, a document issued to a select few by Queen Elizabeth II – and the British go bonkers over anything Royal.

At the opposite pole of professionalism stands the Young Interpreter Scheme (YIS). This is an organisation, indeed a whole movement, sponsored by one of the education authorities in Southwest England, that exists to help integrate pupils whose first language isn't English. There are hundreds of thousands of them in today's UK schools. The youngsters who enter it are given guidance but they aren't trained interpreters and they aren't remunerated. However their tasks inevitably include a good deal of interpreting between their peers and between pupils and school staff. YIS and its life and soul Astrid Dinneen have been commended many times on this blog; to find the posts, enter YI in the 'Search This Blog' box on the right.

Now the two have come together brilliantly. The CIOL has awarded YIS its most outstanding annual recognition, the Threlford Memorial Cup. Congratulations to YIS for its exemplary work and opportunities for young Natural Interpreters, and to the CIOL for recognising it.

Image

Astrid Dinneen receives the award on behalf of YIS, 2018.

Source:

Chartered Institute of Linguists. CIOL awards. Click [HERE] or go to https://www.ciol.org.uk/awards.

Friday, December 7, 2018

Translational Licence for Conference Interpreters

Three posts ago I introduced the term translational licence (TL) to mean the divergences from the source text that are commonly allowed to translators (accidental errors and omissions excluded). To retrieve the post, enter licence in the 'Search This Blog' box on the right. Recently a friend who's a skilled literary translator told me that she makes "small corrections for greater acceptability," It's a good example. A lot of emphasis is put in the translatology literature on closeness to the source (aka fidelity, completeness), and students and examination candidates are penalised for not achieving it. But they aren't taught about the ways, nor to what extent, they may overrule it.

Admittedly there are circumstances where there is no such licence. When I was translating medical school transcripts they were vetted for any discrepancy, and the slightest difference would result in my translation being sent back to me. But those texts were exceptional because of their legal implications, and a far cry from everyday messages or the creative art of literary translation.

Moreover the degree of licence varies not only with the type of text but also according to the culture and the times and even with the type of reader. As T. S. Eliot said, "Each generation must translate for itself."

Now let's take a look at another application of TL: conference interpreting. I learned the hard way that it operates there too, and here's how it happened.

I was interpreting at an international conference of journalists in Ottawa. After the plenary, the participants split up into small groups in side rooms that were not equipped for simultaneous interpreting. The interpreting therefore had to be done in consecutive. I was assigned to a group that was addressed in French by a lady journalist from France. She spoke for about ten minutes. As I had learned to do, I took notes of what she was saying. She was a perfect speaker from my point of view: clear articulation, logical and not too fast. So I was able to note down everything she said. When she'd finished, I took my notes and translated them all. It likewise took ten minutes. Then I turned to her, expecting her to be pleased. Not at all. On the contrary, she scowled and hissed, "Mais monsieur, vous n'aviez pas besoin de dire tout ça!" (My dear sir, you didn't have to say all that again.) I was deflated. But later I had an opportunity to speak with her, so I asked her what I ought to have left out. She replied, "Vous êtes interprète. C'est votre affaire." (You're an interpreter. It's up to you,)That day I learned that conference interpreters have a licence to abbreviate provided the omission doesn't disrupt the message. And thus I would teach my students to do so. For example, I taught them that if the speaker gives three examples of something, it's probable most of the audience is only paying attention to two of them and so the interpreter can skip the third. In simultaneous interpreting, this is a useful 'trick of the trade' for keeping up with the speaker.

Lest you think my experience was unique, let me add that a university colleague of mine, a senior Canadian parliamentary interpreter, used to reduce the mark he awarded if a student's consecutive interpretation wasn't substantially shorter than the original.

Here's another example.

Every interpretation teacher gets asked what to do if the speaker utters something insulting, vulgar, obscene or blasphemous. In court interpreting, it must be reproduced whatever the interpreter feels about it. But the conference interpreter has licence. There the interpreter should follow his or her own standards and conscience and avoid aggravating bad feelings.

Though TL is forbidden in some contexts, it's so prevalent that it qualifies as a quasi-universal of both written and oral translation.

Sunday, November 25, 2018

Jonathan Downie's "Still Thinking"

The purpose of this post is to draw your attention to somebody else's blog. It's the fairly new blog of Dr. Jonathan Downie of Edinburgh, which he calls Still Thinking. He has me still thinking. Indeed I've put an answer there to his latest post, which is about the preponderance of conference interpreting in the research on interpretation. Jonathan is a professional translator-interpreter who specializes in the study of church interpreting, in which field he is currently the doyen, In 1914 he contributed a post on that topic to this blog, which you can retrieve by entering Downie in the Search This Blog box on the right. The URL for Still Thinking is https://jonathandownie.wordpress.com/ or click [HERE].

Monday, November 12, 2018

Natural Translation in Africa

Not much has been published about natural translation (NT) in Africa apart from church interpreting. African church interpreting was first described on this blog in 2009; to find the post, enter Buea in the Search This Blog box on the right. It pains me to read about the language-based conflict that's raging in that part of Cameroon today. In 2009 Cameroon appeared to be a model of linguistic convivience.

Earlier, in 1995, an African student of mine, Christiane Lozès-Lawani, presented a groundbreaking thesis about schoolchildren interpreting in her native country, Benin (see below). It was groundbreaking not only because of NT but also because of her method of eliciting it from children by story telling, and in a way that was typically African..

I was reminded of the above by an article that recently crossed my electronic desk, Importance of translation in contemporary Ghana (see below). Actually it's mostly not about NT but about the need for trained translators and interpreters. It's noteworthy that its author, Dr. Cudjue, includes among the professionals bilingual secretaries, a class of translators that's numerous in my own country, Canada, too, though insufficiently recognised. And it's of interest to Africans to know that there's a training programme at the School of Translators of the Ghana Institute of Languages in Accra, so they don't necessarily have to go to Europe or America for it. The Institute also has a School of Blingual Secretaryship. And another initiative that other schools might well look at is its classes for high school students. Why wait for university to improve young people's translating skills? But of particular interest to us is the article's introductory paragraph, which is very telling with regard to NT (emphasis added):

"Due to its colonial experience and the creation of artificial borders, Ghana finds itself face-to-face with a linguistic reality. The fact that the country is sandwiched between Francophone countries, namely Togo, Burkina Faso and Cote d’Ivoire, has a lot of implications for economic, industrial, political and socio-religious activities.Sources

"One of the simplest ways of defining translation is 'rendering the meaning of a text into another language in the way that the author intended the text' (Newmark 1988). This definition implies then that anybody, including a child, who is delivering a message, for example, from one language into another is involved in translation.

Thus, given the colonial experience that Africans have gone through and the linguistic legacy that has been bequeathed to them, their daily communication is dominated by the process of translation."

Alfred B. Cudjoe, Importance of translation in contemporary Ghana. Graphic Online, 22 October 2018. https://www.graphic.com.gh/features/opinion/importance-of-translation-in-contemporary-ghana.html, or click [HERE].

Christiane Lozès-Lawani. La traduction naturelle chez des enfants fon de la République du Bénin. [Natural Translation by Fon Children in Benin]. Unpublished M.A. dissertation, School of Translation and Interpretation, University of Ottawa, 1994. Advisor Brian Harris. 181 p. Available from ProQuest-UMI, order no. MM04903. In French, but an English abstract is available at https://ruor.uottawa.ca/handle/10393/10118 or click [HERE].

Image

Benin school children. Source: English International School, Cotonou

Saturday, October 27, 2018

Translational Licence

This is to introduce a new term into translation studies aka translatology. It's translational licence (TL). Beware! It has nothing to do with licence in the sense of an official document, nor for that matter with translational in its medical sense. It's licence as used in the literary term poetic licence. That is to say, "the act by a writer or poet of changing facts or rules to make a story or poem more interesting or effective.."

In this case, for "writer or poet" substitute translator; for "facts" substitute the original text; and for "rules" substitute the current norm that a translator should stick as closely as possible to the content and manner of that text.

You can see that the new term therefore has a connection with a much older term, free translation. But free translation is the product or process, whereas TL is a loophole in the norms that allows it, and even encourages it if the free translation succeeds with readers. As for that criterion of success, 'the end justifies the means.'

Notice that it does not cover mistakes. TL is something that the translator takes advantage of knowingly and intentionally.

It can best be explained by an example. The following is a famous one.

Edward Fitzgerald's nineteenth-century translation of the Rubai'iyat (quatrains) by the eleventh-century Persian astronomer-poet Omar Khayyam is one of the best loved poems in the English language. As much loved in English as it is in Persian. Yet nobody should be under the illusion that it's an accurate translation. Certainly Fitzgerald, who learnt Persian for the purpose, never claimed it. On the contrary, he said in a letter to a friend that he had "transmogrified" it. (Transmogrify means "transform in a surprising or magical manner.") He was not above inserting verses that were entirely his own invention. So he knew what he was doing and he assumed the concept that is expressed by translational licence.

A classmate and friend of mine when I was a student at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London was Peter Avery. Peter was studying Persian, but we were brought together because students of Persian also had to learn some Arabic.He was later to become Lecturer in Persian at King's College, Cambridge and died in 2008. Though he didn't deny the poetic value of the Fitzgerald version, it irked him that English readers never got from it the true feeling of the Persian, because it was veiled by Victorian sentiment and versification. So he did his own more accurate translation and got together with a poet, John Heath-Stubbs, to polish it.

"It seemed important to try and convey the baldness of the originals. Past translations of Persian verse have often tended to blur and soften the hard directness of the Persian, allowing a sentimentality quite absent from the original to intrude. It is hoped that these translations will answer the question a Persianist is often asked: 'What do the Persian originals of the ruba'is really say? On the other hand, there is no need to disparage the famous version of Edward Fitzgerald. His work is more in the nature of a fantasia than a translation. It is often very free and occasionally not precisely accurate. Fitzgerald's poetic intuition guided him aright in divining the essentially sceptical and unorthodox nature of the Persian poet's thought, but he was also the champion of such Augustan poets as Dryden and Crabbe… His study of them gave to his work on Persian originals a concision and wit which were entirely appropriate."Here's a small sample of what this is all about. First a quatrain in the Avery-Heath Stubbs translation and then in Fitzgerald's.

I need a jug of wine and a book of poetry,

Half a loaf for a bite to eat,

Then you and I, seated in a deserted spot,

Will have more wealth than a Sultan's realm.

A book of verse beneath the bough,

A jug of wine, a loaf of bread and thou

Beside me singing in the wilderness,

O wilderness were paradise enow.

Fitzgerald's 'conceits' are obvious.

And another:

When we were children we went to the Master for a time,

For a time we were beguiled by our own mastery.

Hear the end of the matter, what befell us:

We came like water and we went like wind.

Myself when young did eagerly frequent

Doctor and Saint, and heard great Argument

About it and about: but evermore

Came out by the same Door as in I went.

In conclusion, say what we will as academic linguists, Fitzgerald retains his popularity thanks to translational licence and clever poetry, whereas the Avery-Heath Stubbs translation has been remaindered.

There's a clue to Fitzgerald's success in another term that was discussed on this blog fairly recently, namely translator's affinity (to retrieve the post, enter affinity in the Search This Blog box on the right). It's defined there as "empathy with the original author." Though Omar and Fitzgerald were far apart in time and place, they were kindred spirits.

Sources

The Cambridge English Dictionary, for the term poetic licence.

Peter Avery. Wikipedia, 2018.

Omar Khayyam. The Ruba'iyat of Omar Khayyam. Translated by Peter Avery and John Heath-Stubbs with a long Introduction by Peter Avery. London: Allen Lane, 1979. Penguin Classics paperback edition 1981.

Omar Khayyam (1048-1131). Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam the Astronomer-Poet of Persia / Rendered into English Verse. 1st edition. Translated by Edward FitzGerald. London:

Quaritch, 1859. Full text with notes from 2nd edn at www.theotherpages.org/poems/rubaiya1.html

or click [HERE].

Image

Omar Khayyam by the great illustrator Edmund Dulac, 1909. Source: David Brass Rare Books.

Tuesday, October 9, 2018

El Nou d'Octubre, Valencia Day

Today. the Ninth of October (el Nou d'Octubre), is the national day of the Valencians, a holiday throughout the Valencian Community, which consists of the Spanish provinces of Valencia, Alicante and Castellón. It commemorates the bloodless entry by the Christian monarch James I into the Moorish city of Balansiyya in 1238. James was king of Aragon; that's why the flag of Valencia, the Senyera (shown above) is based on the heraldic arms of Aragon.

In previous years, this blog has celebrated the day with a historical post about it. This year here's something different: a brief introduction to the Valencian language. It takes the form of the lyrics to the Valencian national anthem. There's a truly rousing performance of it on YouTube, sung by the popular Valencian singer Francisco; and with it the lyrics in Valencian and Spanish. To see it and listen to it, click [HERE] or go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=esDfiT4H_XM. It's accompanied by a typical Valencian band (banda); there's one in every town and village of any size, often with a music school.

There are Wikipedia articles on Senyera and James I of Aragon.

Sunday, September 30, 2018

International Translation Day 2018

This day, 30 September, has been declared International Translation Day by UNESCO and the International Federation of Translators. The date was chosen because it's the feast of St. Jerome. I ought to write something original for the occasion, but as my thoughts are elsewhere at the moment I'll repeat, with a few tweaks, a post that appeared in this blog on a previous 30 September some years ago.

Today is the feast of St. Jerome, the patron saint of translators. He was born in Dalmatia in 347. He's the patron of Professional Expert Translators, that is, because he had to be a multilingual expert for his work on translating the Bible (the so-called Vulgate version) and he was a professional in that he was commissioned to do it by Pope Damasus I. That’s why associations of professional translators around the globe celebrate today as International Translation Day. It’s perhaps ethnocentric to choose the feast of a Christian saint for International Translation Day, but never mind, for he was a great translator. Furthermore, he had definite views about translating and he put them into a long epistle defending them, his Letter to Pammachius on the Best Method of Translating.

The oft-quoted key sentence in the Letter is:

Today I reflect, therefore, that we’re commemorating a religious translator. I’ve long been dismayed at the lack of interest shown in this branch of translation by our university professors of translation studies. When they introduce it into their graduate programmes, they usually treat it historically and ignore its continued contemporary vibrancy, which among other things has given us Eugene Nida’s classic Toward a Science of Translating. A great many of them are concerned these days with the cultural causes and effects of literary translation, but don’t they realize that religious translation has had an even greater impact on culture? Why so? Because religion moves the masses.

From my 20 years at the University of Ottawa, I can only recall one thesis on the Bible or any other religious translation – and that was on St. Jerome. We were once approached by the Wycliffe organization of Bible translators to host a summer school for them, and none of my colleagues was interested.

So I think I may return to the topic, because it has many connections with Non-professional Translation. But to conclude, here’s an old Canadian joke.

Well the old man, who was probably a Protestant anyway, certainly didn’t know about Jerome’s Catholic Latin. But the point of the story is, of course, that many people aren’t even aware that the Bible they are reading is a translation – far less that it’s often the translation of a translation. Indeed it’s always a translation of a translation in part: Christ, for example, spoke in Aramaic and his words were translated into Greek and from there to Latin and from Latin to the European vernaculars, and from those to the indigenous languages spoken in the colonies, so on. It may well be the longest of all the chains of ‘relayed’ translations, and there have been important spin-offs from it like the invention of writing systems by missionaries for languages that didn’t have one. At Paul's behest, Christ's disciples had to interpret into the languages of the nascent Christian communities, and they were assuredly not professionals.. Someone might well do a survey of people’s awareness of it.

References

Jerome. Wikipedia, 2018.

The full Latin text of the Vulgate is available on the web, intercalated with a famous English translation of it, the Douay-Rheims Bible (1582-1610). It’s at http://vulgate.org. It also has Jerome's fine defensive Preface:

Available free online at Scribd.

Image

Saint Jerome in his study by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1448-1494). Source:Wikipedia.

The oft-quoted key sentence in the Letter is:

Not only do I admit, but I proclaim at the top of my voice, that in translating from Greek, except from Sacred Scripture, where even the order of the words is of God’s doing, I have not translated word for word, but sense for sense.People focus now on the last part of the pronouncement (putting meaning before words) because it supports the popular norm for 'good' translation; but in religious translating "God's doing" is also important. It explains why many Muslims are against any translation at all of the Koran.

Today I reflect, therefore, that we’re commemorating a religious translator. I’ve long been dismayed at the lack of interest shown in this branch of translation by our university professors of translation studies. When they introduce it into their graduate programmes, they usually treat it historically and ignore its continued contemporary vibrancy, which among other things has given us Eugene Nida’s classic Toward a Science of Translating. A great many of them are concerned these days with the cultural causes and effects of literary translation, but don’t they realize that religious translation has had an even greater impact on culture? Why so? Because religion moves the masses.

From my 20 years at the University of Ottawa, I can only recall one thesis on the Bible or any other religious translation – and that was on St. Jerome. We were once approached by the Wycliffe organization of Bible translators to host a summer school for them, and none of my colleagues was interested.

So I think I may return to the topic, because it has many connections with Non-professional Translation. But to conclude, here’s an old Canadian joke.

You have to know that there were, and indeed there still are, many ‘rednecks’ in English Canada who regard the official requirements for the use of French as an intolerable imposition. The more open-minded son of one such man tells his father that times are changing and he’s decided to learn French. “Why in Heaven’s name learn another language?” asks the father. “If English was sufficient for God when he composed the Bible, it ought to be enough for you.”

Well the old man, who was probably a Protestant anyway, certainly didn’t know about Jerome’s Catholic Latin. But the point of the story is, of course, that many people aren’t even aware that the Bible they are reading is a translation – far less that it’s often the translation of a translation. Indeed it’s always a translation of a translation in part: Christ, for example, spoke in Aramaic and his words were translated into Greek and from there to Latin and from Latin to the European vernaculars, and from those to the indigenous languages spoken in the colonies, so on. It may well be the longest of all the chains of ‘relayed’ translations, and there have been important spin-offs from it like the invention of writing systems by missionaries for languages that didn’t have one. At Paul's behest, Christ's disciples had to interpret into the languages of the nascent Christian communities, and they were assuredly not professionals.. Someone might well do a survey of people’s awareness of it.

References

Jerome. Wikipedia, 2018.

The full Latin text of the Vulgate is available on the web, intercalated with a famous English translation of it, the Douay-Rheims Bible (1582-1610). It’s at http://vulgate.org. It also has Jerome's fine defensive Preface:

The labour is one of love, but at the same time both perilous and presumptuous; for in judging others I must be content to be judged by all; and how can I dare to change the language of the world in its hoary old age, and carry it back to the early days of its infancy? Is there a man, learned or unlearned, who will not, when he takes the volume into his hands, and perceives that what he reads does not suit his settled tastes, break out immediately into violent language, and call me a forger and a profane person for having the audacity to add anything to the ancient books, or to make any changes or corrections therein?I was introduced to Jerome’s Letter to Pammachius through the English translation made in the 70s by my Ottawa colleague Louis Kelly, who now lives in retirement in Cambridge, England. Unfortunately that translation is not now available, but Kelly discusses the Letter in his book The True Interpreter: A History of Translation Theory and Practice in the West, which is on sale at www.amazon.co.uk.

The Nida classic is:Eugene A. Nida (American Bible Society). Toward a Science of Translating / With special reference to principles and procedures involved in Bible translating. Leiden: Brill, 1964. 331 p.

Available free online at Scribd.

Image

Saint Jerome in his study by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1448-1494). Source:Wikipedia.

Thursday, September 20, 2018

We Can All Be Polyglots

|

| Cardinal Mezzofanti |

A friend in Paris has sent me a recent article from an unexpected source, The New Yorker. It's by one of their well-known staff writers Judith Thurman and its title is The mystery of people who speak dozens of languages. In what follows I will try to dispel some of the mystery.

Pruned of its New Yorker chattiness, the first part of the article gives interesting information about famous polyglots in the past:

* According to Pliny the Elder, the Greco-Persian king Mithridates VI, who ruled twenty-two nations in the first century B.C., administered their laws in as many languages, and could harangue in each of them.Those were champions, so-called hyperglots. Their achievement was the fruit of many years of learning. But scarcely less remarkable is the achievement by the little girl Bella Devyatkina who was described last month on this blog and who could converse in seven languages at the age of four. Yet the underlying reason why all of them could do what they did is the same. It's that human psychology and the physical human brain are built from infancy, perhaps from birth, for multilingualism (bilingualism being a special case of multilingualism and not the other way round.) Bella's mother insists that her daughter, for all her precocity, is not a genius. It's just that she has been put in situations and relationships where she responds to the motivation of receiving a present from speakers of other languages.

* Plutarch claimed that Cleopatra very seldom had need of an interpreter, and was the only monarch of her Greek dynasty fluent in Egyptian.

* Elizabeth I also allegedly mastered the tongues of her realm—Welsh, Cornish, Scottish, and Irish, plus six others [including the language of her enemy, Spanish].

* The prowess of Giuseppe Mezzofanti (1774-1849) is more astounding and better documented. Mezzofanti, an Italian cardinal, was fluent in at least thirty languages and studied another forty-two, including, he claimed, Algonquin. In the decades that he lived in Rome, as the chief custodian of the Vatican Library, notables from around the world dropped by to interrogate him in their mother tongues, and he flitted as nimbly among them as a bee in a rose garden.

* Thurman misses out the 18th-century English orientalist and translator Sir William Jones, who was reputed to know 26 languages.

Scientists and philosophers agree that language is one of the marvels of human evolution, No other animals have anything comparable. To it has been added another evolutionary marvel: the ability to learn multiple languages. The examples quoted above suggest that in principle there is no limit to their number. Yes, there are practical limits; the time we can devote to learning them and the length of our lives for instance, and the amount of contact we have with other-language speakers . And there are also psychological constraints, in particular motivation, without which we may be unwilling to work at it. But not the structure of our minds.

There are different degrees of multilingualism, which makes it difficult to compare polyglots. Full multilingualism requires much more than knowing the grammars and vocabularies of the languages. The functioning multilingual can do the following:

a) Keep the languages separate. Actually very young bilinguals are prone to mixing their languages in the same sentence or utterance, a phenomenon linguists call code switching. Typically this weakness disappears around age three, but vestiges of it remain throughout life. We multilinguals are all used to occurrences of leakage or interference between our languages; for instance the common phenomenon of false friends. However, they dwindle to a frequency where they don't hamper communication.There are several ways in which we can learn languages. For example, "Mezzofanti, the son of a carpenter, picked up Latin by standing outside a seminary, listening to the boys recite their conjugations." I learnt my mother language, English, unconsciously and effortlessly from birth as I'm sure you did; three languages (French, German, Latin) in compulsory formal courses at school from age 11; one (Arabic) in formal university courses from age 18 because I was interested in it and thought it would help me get a job; and two others later (Spanish and Valencian) without ever taking a course in them but from elementary teach-yourself books and everyday conversation with native speakers with whom I was working. Apart from English, age had little to do with it. If I went to live in another country, even at my advanced age, I wouldn't hesitate to learn its language. Of course, as with any natural skill, there is a pathology: a minority of people may have learning problems, and language learning becomes more difficult, requires more conscious effort, once the stage of early plasticity is passed. It has seemed to me, though, that most of my English and Canadian compatriots who say they can't learn a foreign language are like people who don't learn to swim because they're afraid of the water.

Just how the separation is maintained is a matter of disagreement. Some psycholinguists believe we keep our languages in separate drawers, as it were, and take them out and activate them as we need them. Others think that on the contrary they are all present in our working minds but we suppress the ones we don't need at the moment.

b) Switch between the languages. This may be done at will and almost instantaneously; or the switch may be triggered automatically by a stimulus, for instance when answering a question in the language in which it is asked.

c) Use the languages appropriately to express the thoughts we want to convey or to understand what others are telling us. It may be, however, that we aren't equally competent at this in all our languages; it depends very much on the experience we've had in using them.

d) Use the languages in ways that are appropriate for the speaker/writer and for the addressee. For more about it and the weakness of machine translation in this respect, enter pragmatics in the Search box on the right.

Sources

Judith Thurman. The mystery of people who speak dozens of languages. The New Yorker, 3 September 2018. My thanks to Philippe Lambert for sending it.

William Jones (philologist). Wikipedia, 2018.

Image

Cardinal Guseppe Mezzofanti.

Saturday, August 11, 2018

A 4-Year-Old Polyglot Translator

Bilingual young children are commonplace in the village where I live. They speak Spanish and Valencian. Moreover, once they go to school they start learning English, so they become trilingual though their English is far from fluent. But a four-year old child who can converse in seven languages, and read from a story book in most of them – that is a rarity. Yet it's the achievement of a bouncy little Russian girl called Bella Devyatkina. Seeing is believing, so click [HERE] or go to https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=bella+devyatkina

to see her performing on TV. There you will find a whole collection of videos of her.

Her languages are her native Russian plus Chinese. English, French, Italian, Spanish and – surprise – Arabic. What is most extraordinary is not the number of languages; an adult who accompanies her on one of the videos speaks ten and the eighteenth-century orientalist Sir William Jones is reputed to have learnt 28. Multilingualism is one of the universal miracles of human language evolution. Why are we endowed with the possibility of speaking more than one language? Furthermore it's the ability not only to speak the languages correctly but also to use them appropriately. When Bella is asked a question she answers unhesitatmgly in the language in which it is asked. This is a bilingual's normal instinct. But when she is addressed by a succession of interlocutors using different languages, it requires her to change her language too. Bilinguals' apparently effortless ability to switch between their languages is yet another miracle and there's no agreement about how this is achieved. Bella's ability to do all this at such a young age and with so little exposure to her languages other than Russian supports Noam Chomsky's hypothesis that we are born with an inherited language acquisition mechanism.

There are some other interesting things to notice in Bella's performances.

1. She makes clean switches; she doesn't mix her languages. Up to the age of three, bilinguals tend to mix features of two languages in the same sentence (which the linguists call code switching). At age four, Bella is beyond this.

2. Her languages come from different language families: Slavic for Russian; Romance for French, Italian and Spanish, Germanic for English and German; Semitic for Arabic. The distance between the languages doesn't seem to matter.

3. She reads fluently in all her languages except Arabic. Reading skill is not so extraordinary, but still four years old is very young. She can also sing in them. Singing songs requires memory for melody as well as for words..

4. Bella doesn't use the foreign languages in her everyday life. Hers is not a language brokering situation. So she doesn't have the motivation that real communication need provides in language brokering. Instead, motivation is provided by accustoming her to expect a present each time she gets an interchange of conversation right. Notice that in one of the videos she begins by asking, "Where is my present?".

Is Bella an extraordinarily gifted prodigy, as the TV shows tend to suggest? (Compared with this child I feel like an idiot," was the comment from one viewer of the Russian TV show, which is called Amazing People.) Not so, says her mother, and likewise the man who speaks ten languages and accompanies her on one of the videos. What's extraordinary is not her ability but her education. She was taught mostly by what's called the OPOL method, which means One Person One Language. It's the method used by the groundbreaking French linguist Jules Ronjat for his son Louis in the early years of the last century (see Sources below). Bella's mother too is a linguist. There's a full account of the teaching process in the Arkhangelskaya article listed below.

One question remains that's important for the Followers of this blog: Can Bella translate? The OPOL method avoids encouraging translation, so it's not surprising that there are no overt tests of it on the videos. But it has been documented since the time of Ronjat that four-year-olds can translate, and we can indeed find a proof that Bella can do it. It comes in the video where, having read fragments of stories in her range of languages, she answers questions about them in Arabic. Her answers are too summary to constitute what some people would consider translations, but we can't apply adult criteria to a child of four. She meets the fundamental characteristic of translation, which is the transfer of information from one language to another.

Thank you Bella, little darling!

Sources

Svetlana Arkhangelskaya. 4-year-old Russian girl speaks 7 languages.How did she do this? Russia Beyond, 28 October, 2016. Click [HERE] or go to

https://www.rbth.com/science_and_tech/2016/10/28/4-year-old-russian-girl-speaks-7-languages-how-did-she-do-this_642979

One person, one language. Wikipedia, 2016.

Jules Ronjat. Le développement du langage observé chez un enfant bilingue [Language development in a bilingual child]. In French only. Paris: Champion, 1913. 155 p. Click [HERE] or go to https://archive.org/details/ledveloppement00ronjuoft.

Friday, July 20, 2018

The Queen of Spain Thanks Her Tactile Interpreters

A little over a hundred kilometres to the south of where I live lies the resort town of Benidorm. IMHO it's a blight on the Spanish coastal landscape, famous for cheap package beach holidays and jnfamous for boozy Britons; though to be fair it also has a colony of respectable expatriates. Amongst the latest news from Benidorm is the following:

A shooting in the heart of Benidorm’s nightclub district on Wednesday night caused panic among innocent holidaymakers and resulted in a police lockdown of Calle Mallorca, known as The Square among Britons.

So it took an extraordinary event a few days ago to bring Queen Letizia of Spain to Benidorm for the first time. That event was the 5th General Assembly of the World Federation of the Deafblind and 11th Helen Keller World Conference.

It may come as a surprise to read that the deafblind community is large and organised enough to support an international conference in a luxury hotel, but there are an estimated half a million deafblind people in the world and the conference has been acting as a forum since 1977.

The most obvious peculiarities of such a conference are first that all the participants need a personal interpreter in order to interact with other people and with the world around them; and second that, since they are denied sound and sight, the two usual media of interpreting, they must fall back on another of the human senses: touch. Interpreters who communicate by touch are called tactile interpreters, and the signs that they use are called haptic signs. (Tactile from Latin and haptic from Greek, both meaning touch.)

One classic, well-known haptic sign system is braille, which uses patterns of raised dots. perceived through the fingers, to represent the written alphabet. Like some other systems, it's used at two levels, elementary and advanced. The advanced level includes many short cuts and abbreviations. I know, from having had a blind colleague, that an advanced reader who's been using it since childhood can read a braille text as fast as a sighted person can read a printed one.

Tactile interpreters are one kind of interpreter who must be skilled in doing more than just transmitting language. Their clients being sightless, they must in addition convey some description and explanation of the context by an analogue of what is elsewhere called audio description.

The most famous tactile interpreter was Anne Sullivan (1866-1936). She was the interpreter, amanuensis and lifelong companion of the American deafblind writer, political activist and lecturer Helen Keller (1880-1968). In spite of Helen's disabilities, they travelled the world together. Anne had managed to obtain an education at the Perkins School for the Blind in Boston, where she became a teacher and learned the American Manual Alphabet, which can be used as a haptic code for fingerspelling (see Sources below). She was therefore not completely untrained when she was taken on as Helen's teacher. But Helen and Anne had less known though well documented predecessors, and there the story was somewhat different. Helen's predecessor was another American, Laura Bridgman (1829-1889). She too was a Perkins graduate 50 years before Helen. She did receive ephemeral fame when Charles Dickens met her on his American tour and wrote about her. As a young child,

Her closest friend was a kind, mentally impaired hired man of the Bridgmans, Asa Tenney, whom she credited with making her childhood happy. Tenney had some kind of expressive language disorder himself, and communicated with Laura in signs. He knew Native Americans who used a sign language, (probably Abenaki using Plains Indian Sign Language), and had begun to teach Laura to express herself using these signs when she was sent away to school.It's clear that. in the absence of any training, 'Uncle Asa' – as he was known to the family – was a Natural Sign Language Interpreter. Later, at Perkins, Laura was taught braille.

Since the tactile interpreters don't yet carry enough weight to form their own international organization, they have been taken under its wing by the World Association of Sign Language Interpreters, the organisers of the Benidorm assembly. Aong the goals of the WASLI are to

elevate awareness of Deafblind interpreting at conferences on a global scale [and] advocate for equal pay and working conditions for interpreters working with Deafblind people at conferences.They deserve it.

Queen Letizia took pains in her closing speech to the assembly to give warm thanks to the tactile interpreters who had enabled her to converse with some of the participants.

Sources

Briton injured in gangland shooting. Costa News, 5 July, 2018.

World Federation of the Deafblind. World Conference 2018. Click [HERE] or go to http://www.wfdb.eu/wfdb-world-conference-2018/

Anne Sullivan, Fingerspelling, Helen Keller and Laura Bridgman Wikipedia, 2018.

Edith Fisher Hunter, Child of the Silent Night: the Story of Laura Bridgman. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1963. Excerpts at Google Books.

Kelli Stein et al. WASLI DeafBlind Interpreter Education Guidelines. Click [HERE] or go to https://wasli.org/special-interest/deafblind-interpreting

Image

Deafblind Catholic priest Fr Cyril Axelrod signing to interpreter Rita Vella.

Source: Malta Deaf Association

Wednesday, June 27, 2018

Was Koko, the 'talking' gorilla, bilingual?

Many people felt a pang of sorrow last week at the news that the most famous and most studied of gorillas, Koko, had died peacefully in her sleep in California . Koko herself had felt such a pang when she was given the news that first her beloved adopted kitten and later her friend the actor Robin Williams had died. How do we know that? Because Koko communicated her feeling to her carers in her language, Gorilla Sign Language.

The extent and nature of Koko's language ability is a matter of special interest to the Followers of this blog. It's long been hotly disputed, though it's generally agreed she did have some and that she used the medium of sign language to transmit it. The signs she used were drawn from the American Sign Language (ASL) widely used by the deaf. It wasn't the full ASL – therefore it's misleading to say that she "mastered ASL" as some obits have done – but a modified subset of it, a baby sign language. Still, she learnt 1,000 to 2,000 signs -- accounts vary -- which is quite a big vocabulary.She wasn't the first primate to learn some sign language -- it had been done by chimps -- but she was the first gorilla.

The amount of ASL that Koko knew is unimportant. It probably wouldn't have been of any use to her to know more. Her cognitive ability was equivalent to that of a young human child, and in general people only learn as much language as they need at their age. Nobody knows the whole of, say, English. However, there's another feature of Koko's language that's of interest to translatologists. Although she only produced sign language, she could understand some spoken English. Apes don't possess the organs of phonation needed for producing the sounds of English so she had no possibility of speaking it; but it's not uncommon for humans also to be able to understand a language yet not speak it. What is documented is that Koko could be asked a question in English and answer it in sign language.

In a 1978 paper on translation by young children (see Sources below) we called this kind of interaction bilingual response. It's a variety of what linguists code switching. Can it be considered a kind of translating? In the 1978 paper we classed it among the pretranslation phenomena in children which precede translation as it is generally understood. But translation or not, it involves a transfer of thought between symbolic systems. It therefore implies that Koko was capable of what we have elsewhere called conversion. (For more on conversion, enter the term in the Search box on the right,)

There are many other indications that animals, and not only primates, are capable of conversion; but Koko's 'bilingualism' is an important one. It raises the tantalising question of whether some of the seeds of translating may already be planted in lower animals than humans

Sources

Koko: Gorilla death coverage rekindles language debate. BBC News, 22 June 2018. Click [HERE].or go to https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-44576449

Washoe (chimpanzee). Wikipedia, 2018. Click [HERE]. or go to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Washoe_(chimpanzee)

Brian Harris and Bianca Sherwood. Translating as an innate skill. 1978. Click [HERE]. or go to https://independent.academia.edu/BHARRIS

Monday, June 11, 2018

The Ethos of School Language Brokering

First a terminology round-up. The term language brokering came into use in the 1990s in the USA. The story of its later subdivision into child language brokering, etc., has already been told on this blog. To find the relevant post, enter school language brokering in the Search box on the right. As usual, the thing existed before the word for it: an early paper a Canadian school teacher and myself classed it as a form of "community interpreting" (see Sources below). As that early paper showed, the ability to interpret is not the preserve of exceptionally gifted youngsters; it's quite everyday in immigrant communities.

Child and adolescent language brokering in schools has been commented on favourably in this blog. However, there are admittedly some disadvantages and dangers. They are discussed extensively in the Cline-Crafter report listed below. It's therefore desirable for a school or related organization that uses students as language brokers to have an explicit policy that lays down what the latter can and can't do. The Cline-Crafter team has produced a Guide to Good Practice. Here's a more recent 'job description' from the EMTAS movement, which has pioneered SLB in the UK.

"Young Interpreters are trained to welcome new arrivals and make pupils with EAL feel settled at school. For instance, Young Interpreters might give tours of the school, play a game at break time, demonstrate routines, take part in activities which promote multilingualism, etc. The role of Young Interpreter is not to replace bilingual staff or professional interpreters. Pupils operate in situations which only require everyday language and do not miss out on their own learning to help others.This is a view of SLB that goes beyond simple transposition of language and recognises brokers as facilitators of understanding between diverse cultural groups.

"At times, Young Interpreters may rely on their languages when these are shared with their buddies. At other times, they will tap into other skills to welcome pupils with whom they do not share a language: pupil-friendly English, visuals, body language, etc. This means all new arrivals can feel welcome from the start, even when no one else speaks their language. Young Interpreters therefore interpret in the broad sense of the term but most importantly, they are empathetic friends.

"As such, Young Interpreters can and should be selected from amongst bilingual learners as well as learners who only speak English and who have much to bring in terms of kindness and friendship. By selecting EAL and non-EAL pupils to train as Young Interpreters, the co-ordinator will send strong messages to the whole school community: everyone can welcome new arrivals, from the multilingual to the monolingual."

Sources

Tony Cline (University College London) and Sarah Crafter (Institute of Education, London). Child Language Brokering at School. London: Nuffield Foundation. Click [HERE] or go to http://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/child-language-brokering-school

Astrid Dinneen. What it means to be a Young Interpreter within the ethos of the scheme. Young Interpreters Newsletter, No. 31, Hampshire EMTAS, April 2018. Click [HERE] or go to https://dmtrk.net/YU8-5ITPW-21IFJ1AS41/cr.aspx

Carolyn Bullock and Brian Harris. Schoolchildren as Community Interpreters", 1995. Click [HERE] or go to https://www.academia.edu/3087237/Schoolchildren_as_community_interpreters

Tuesday, May 22, 2018

NPIT4 at Stellenbosch

Today the 4th International Conference on Non-Professional Interpreting and Translation (NPIT) opens at Stellenbosch University near Cape Town. and lasts for three days. It covers many of the topics treated in this blog. The programme is available by clicking [here] or going to http://conferences.sun.ac.za/index.php/NPIT4/index/pages/view/Programme.

As usually happens at such conferences, a few papers creep in that seem to have little to do with the subject. For instance the opening paper Generativity and the Practice of Translation; but appearances can be deceptive. As a whole the papers are wide ranging and draw attention to NPIT in Africa, though I would have liked a balance that had more from the wide world beyond Europe and the USA. One of the pioneers of dialogue interpreting studies, Cecilia Wadensjö of Sweden, is participating.

One paper in particular seems relevant to a topic that was raised on this blog only a few weeks ago and was dubbed inverse child language brokering. (To retrieve the post, enter inverse in the Search box on the right.) It's the paper by Elena Garcia Gandia of the University of Nevada and graduate of my neighbour the Jaime I University at Castellón de la Plana (see below.)

To anyone at the conference who may happen on this post, my best wishes for a happy stay in South Africa.

Reference

Elena Gandia Garcia. Evaluating the training needs of ad-hoc interpreters working with unaccompanied minors who seek asylum in the US. Paper to the NPIT4 Conference, Stellenbosch, 2018.

Saturday, May 5, 2018

Karl Marx Bicentenary

Today, 5 May 2018, is the 200th anniversary of birth of the great German-British sociologist Karl Marx. British? Yes, Marx became stateless and he lived the most productive years of his life in London, where he's buried. I used to walk past his home in the Soho district every day on my way to work, and do my research as he did in the reading room of the British Museum up the road, Moreover his thinking was influenced by what he observed of British commerce and industry in Manchester, where his collaborator and benefactor Friedrich/Frederick Engels ran a successful business, and they would drink together at the Red Dragon pub in nearby Salford.

What makes Marx worth reading now is not his Panglossian prognoses, but his still resonant diagnoses…"The bourgeoisie,” Marx and Engels wrote, beautifully, “has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self- interest, than callous ‘cash payment’. It has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation.”I had thoughts like these while listening to Mark Zuckerberg's Facebook testimony to the US Congress las week.

Marx wrote mostly in his first language, German. His ideas and his influence couldn't have spread as far and as fast as they did without the help of his translators, so it's fitting to draw attention to the latter on this occasion. The early ones were NPIT Marxist acolytes whom Marx and Engels sought out or who did it on their own initiative. There's a tribute to a few of them in a short paper on the academia.edu web page that's the companion to this blog (see below).

And the labour of translating Marx continues, now professionalised, and is probably never-ending. The centre of activity has shifted from Russia, where it was in Soviet days, to China. At the Central Bureau of Compilation and Translation in Beijing, Gu Jinping, a highly professional and highly specialised translator now aged 85, continues to work with his colleagues on translations of Marx and Marxism.

Stuart Jeffries. Two centuries on, Karl Marx feels more revolutionary than ever. Guardian Unlimited, 5 May 2018.

Christopher Hooton. Pub where Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels 'discussed communist revolution' shuts down amid redevelopment. The Independent, 8 August 2017.

Brian Harris. Marx's earliest English translators. Academia.edu, 2010-2017. To retrieve it, click [here].

Xinhua. China focus: for tranlators, Marxist works a lifetime labor of love. Xinhuanet, 8 May 2018. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-05/03/c_137154149.htm.

Friday, April 13, 2018

We Are All Translators

|

| Boguslawa Whyatt |

In a post last October I lamented that "my mission of recognition for the importance of Natural Translation is not yet accomplished and it won't be in the short working life left to me," Then I added, "Hopefully it will be taken up by another generation."

Well, that next generation may already be among us in the person of Prof, Boguslawa Whyatt, head of the Department of Psycholinguistic Stuies at the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan, Poland. The title of her paper in the NPIT collection (see References below) says it loud and clear: We are all translators. A title after my own heart! Here's an abstract, in her own words, of the book on which the article is based.

"The book explores translation as a human skill in its evolutionary perspective from the predisposition to translate to translation expertise. By assuming that the human mind is intrinsically a translating mind all people who know two languages are able to translate but only some develop their natural ability into a more refined skill, fewer choose to acquire translation competence, and few attain the level of expertise. Starting with a thorough analysis of the bilingual foundations on which translation as a human skill is built the natural ability is analyzed and followed by an up-to-date account of translation as a trained skill with the underlying translation competence. To account for the developmental nature of translation as a skill a suggestion is made that the acquisition of translation expertise can be seen as a process of learning to integrate knowledge for the purpose of translating."

Why do I like this so much? First because it starts from the perspective that there is a "predisposition to translate… assuming the human mind is intrinsically a translating mind [and] all people who know two languages are able to translate." It's the basis of the Natural Translation Hypothesis, and before me it was affirmed by the Bulgarian semiotician Alexander Ludskanov, who was perhaps the first to declare, "All bilinguals can translate." Whyatt does not discuss whether the predisposition is in some way inherited, but she does reference my paperTranslating as an innate skill.

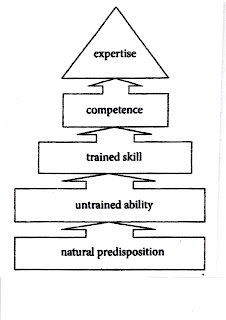

Second, she views the sophisticated skills of expert translators as the outcome of a progression of learning and experience beyond the initial predisposition. Here's her diagram of the process.

This can be compared with the diagram I posted on this blog in 2010; to retrieve it, enter bandies in the Search box on the right. Her diagram does not show a division between the path of formal training and accreditation and that of self-learning by observation and experience. However, she does so in her text. But it's misleading to say about the latter route, as she does, that "it might apply only to some limited communicative contexts or some talented individuals." This category of what I call (following Toury) Native Translators includes. for example, the large and influential tribe of literary translators, few of whom have ever followed a formal course or training in translating. Indeed, even in Whyatt's own data, among the professional (and presumably expert) translators whom she surveyed, only 57.5% attributed their expertise to a "translation training programme" or to "mentoring."

And third, she recognises that translating expertise requires extralinguistic knowledge and cognitive development as well as language proficiency.

In the 40 years since publication of The Importance of Natural Translation, despite what Whyatt describes as "the criticism from translation scholars" with which it was received, a fair amount has been said to support it, and all the more with the emergence of such phenomena as child language brokering and crowdsourcing. Whyatt's article gives a well-written roundup of the research. All serious translatology specialists should read it.

References

Boguslawa Whyatt. We are all translators: investigating the human ability to translate from a developmental perspective. In R. Antonini et al. (eds.) Non-professional Interpreting and Translation, Amsterdam. Benjamins, 2017, pp. 45-64. For the book, click [here].

Boguslawa Whyatt. Translation As A Human Skill: from predisposition to expertise. Poznan: Wydawnistwo Naukowe (Adam Mickiewicz University.Presss), 2012. 447 p., bibliography. Hard to find in libraries but can be ordered from the publisher at http://www.press.amu.edu.pl/.

If you want to follow Prof. Whyatt`s research, see her pages on the ResearchGate and the Academia.edu websites.

Alexander Konstantinov Ludskanov (or Ljudskanov). Prevezhdat chovekat i machinata [Human and Machine Translation], In Bulgarian. Sofia: Nauka i Izkustvo, 1967. There are German, French and Italian translations: see WorldCat..

Brian Harris. The importance of natural translation. 1976. Click [[here].

Brian Harris and Bianca Sherwood. Translating as an innate skill. 1978. Click [here].

Tuesday, April 3, 2018

Inverse Child Language Brokering

Followers of this blog know well what child language brokering (CLB) is, but for newcomers we repeat that it's the interpreting done by children and adolescents, typically from immigrant families, for their family members and other close acquaintances. There's a considerable research literature about it, some of which is listed in the Bibliography of Natural Translation (see References)

However there's practically nothing about the opposite situation where it's adults who interpret for children. Yet this raises a number of questions. How prevalent is it? Do the interpreters adjust their language register to match the age of the children, perhaps even using baby talk? Do they edit and censor the content of the message to make it more suitable or palatable for youngsters? Do they add explanations? And so on.

While looking for examples of CLB on YouTube, I was surprised to find examples also of the opposite. Here's one that's delightful. Most YouTube viewers will understandably be fixated on the child in it, but we should also consider the activity of her interpreter, without whom the interview could not have been conducted. To see it, click [here] or go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ucoo-z26E6s.

For lack of an established term for this kind of interpreting, I propose that we call it inverse child language brokering.

References

Anke Chen and Ellen DeGeneres. 6-year-old piano prodigy wows Ellen. The EllenShow, 2017.

Brian Harris. An Annotated Chronological Biblography of Natural Translation Studies with Native Translation and Language Brokering, 1913-2012. Click [here] or go to https://www.academia.edu/5855596/Bibliography_of_natural_translation

Friday, March 16, 2018

A Ministerial Child Language Broker

There's plenty of material available, some of it on this blog, about child language brokers, immigrant children who act as interpreters for their families and sometimes for other people such as their schoolmates. (To retrieve the blog posts, enter brokers in the Search This Blog box on the right.) However we hear little about what becomes of them later in life. Therefore it comes as a something of a surprise to find one of them as a government minister. The background is the language situation in present-day Britain, where, according to the.minister himself, "There are 770,000 people in England unable to speak English well."

The minister is Sajid Javid MP, a name tand title hat already tell us much. His family came from Pakistan. Now he's the Communities Secretary in the government of Theresa May and "one of Britain's most high profile Muslim politicians."

"Describing his early childhood in Rochdale [a town in Greater Manchester], he said that segregated sommunities meant that women like his mother could spend much of their lives speaking Punjabi and not interacting with people from other ethnic groups.

"I used to go to the doctor's surgery with her -- not because I was ill but because I had to interpret for her. I was six or seven and an interpreter."

Source

Anushka Asthana. Sajid Javid: 770,000 people in England unable to speak English well. Guardian Unlimited, 14 March 2018.

Thursday, March 8, 2018

International Women's Day, 2018

(This post has now been combined with another one to form a short paper on my site in Academia.edu. Its title is "Marx's Earliest English Translators". To read it, click [here] or go to

https://www.academia.edu/36125927/Marxs_Earliest_English_Translators.docx.)

https://www.academia.edu/36125927/Marxs_Earliest_English_Translators.docx.)

Today, 8 March, is, as you're no doubt aware, International Women's Day. Here in Spain there's a Women's Strike (la Huelga feminista) against mistreatment and discrimination. The serious newspapers like El Pais are running stories of women whose contribution to scence, literature and the arts has been downplayed, often to the benefit of their husbands.

In my own experience of Expert Translation, it's been an 'equal opportunity' profession. I worked with more women conference interpreters than men, and at the University of Ottawa I had a majority of female colleagues; and we were all paid on the same fee or wage scales. Lkewise I constantly had a majority of women students. But elsewhere it's not always been so equal.

There have been great women translators. A few, like Constance Garnett, the early English translator of Tolstoy and many other Russian authors, have been amply lauded by their peers and recognised by publishers. (There's a Wikipedia article on her.) Others less so. Back in 2010 there was a post on this blog in recognition of one of the latter, Eleanor Marx Aveling. Here, as a contribution to the Day, is a repetition of that post.

Marx and Daughter

The first volume of Das Kapital was published in German in 1867. He and his alter ego Friedrich Engels had difficulty finding a translator, and it was already in its third German edition before the English translation appeared 20 years later. Engels himself says, in his Preface to the translation:

[A]n explanation might be expected why this English version has been delayed until now, seeing that for some years past the theories advocated in this book have been constantly referred to, attacked and defended, interpreted and misinterpreted, in the periodical press and the current literature of both England and America.At his death in 1883, Marx had left – Engels continues –

a set of MS. instructions for an English translation that was planned, about ten years ago, in America, but abandoned chiefly for want of a fit and proper translator.So Engels then turned to the same socialist lawyer-judge who translated the Manifesto: Samuel Moore of Manchester. Moore embarked on the work, but he wasn’t a Professional Translator:

[B]y and by, it was found that Mr. Moore's professional occupations prevented him from finishing the translation as quickly as we all desired.Therefore a second translator had to be sought. Engels found him right on his doorstep, as it were. He was Edward Aveling, the common-law husband of Marx’s youngest daughter Eleanor (see photo). Aveling too wasn’t a Professional Translator. He was, “a prominent English biology instructor and popular spokesman for Darwinian evolution and atheism.” Engels coordinated and revised the work of the two translators and he details in his Preface the contributions of each.

But there was another translator involved. She’s not credited on any of the bibliographic records; however, tucked away in the Preface is an acknowledgement from Engels:

Mrs. Aveling, Marx's youngest daughter, offered to check the quotations and to restore the original text of the numerous passages taken from English authors and Blue books and translated by Marx into German.She played the role, on that occasion, of what today might be called a Translation Assistant. But she was more important than that. Of all the translators I’ve mentioned, she was the only Professional Translator. Let’s turn to her.

Eleanor ‘Tussy’ Marx (1855-1898) was an early bilingual. She was born and brought up in London, but in a German and Yiddish-speaking household. She also learnt French, perhaps from her father. She became, quite naturally, a militant socialist. She was also an occasional actress. That she was unconventional is shown not only by her personal ‘relationship’ with Aveling but also by her professional work for the avant-garde publisher Henry Vizetelly. She translated Madame Bovary for him, a brave thing to do in prudish Victorian England. She said about it herself,

Certainly no critic can be more painfully aware than I am of the weaknesses...; but at least the translation is faithful. I have neither suppressed nor added a line, a word.She also translated another socially avant-garde writer, Ibsen.

Professional life wasn’t easy for Eleanor. She wrote to Havelock Ellis in 1874, "I need much work, and find it very difficult to get. ‘Respectable' people won't employ me." Vizetelly went to prison for publishing English translations of Zola and Maupassant, and it broke his health. Seems incredible today.

Eleanor had one other important pioneer distinction in the realm of translation. She was an accomplished Native Interpreter of English, French, German and Yiddish, As such, she interpreted for delegates to the International Socialist Workers Congress in Paris in 1889. That makes her an early modern Conference Interpreter. (Large international conferences had only recently been made feasible by the extending network of railway and steamship lines.) Certainly, to my knowledge, she was the first woman Conference Interpreter.

REFERENCES

Karl Marx. Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production.

Volume 1. Edited with a Preface by Frederick [sic] Engels. Translated from the third German edition by Samuel Moore and Edward Bibbins Aveling. London, 1887.

Edward Bibbins Aveling.

http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/bio/family/aveling.htm

Jonathan Kaplansky. Eleanor Marx: translator, interpreter and unconventional Victorian woman. Circuit (Montreal) 66.29-30., 1999. There are other biographies of her in print and on the web

Gustave Flaubert. Madame Bovary. Provincial Manners. Translated from the French édition définitive by E. Marx-Aveling. London: Vizetelly, 1886.

Tuesday, February 27, 2018

Professional Translator versus Expert:Translator: the Case of Malta

This blog has always distinguished between the terms professional translator and expert translator. The defining characteristic of the former is practising translation as a means of livelihood; but professional translators also have other important characteristics that were listed in a post last year. To retrieve it, enter professional in the Search This Blog box on the right. The same post also discussed the difference between the professional and the expert. The general public, on the other hand, conflates the two under the single label professional translator. Understandably so, because if you pay professionals good money for their work, you expect it to be of expert quality. However, those of us with experience in the profession know that 'it ain't necessarily so.' This is possible and even widespread because translating isn't by and large a regulated profession. There are sectors of it that are regulated, for instance court interpreting, but even then only in certain jurisdictions. Elsewhere there is nothing to prevent any bilingual setting herself or himself up as a translator or interpreter and touting for business. Therefore translatologists should be more discriminating in their terminology than the general public.

Recent and not-so-recent events in Malta highlight the danger of confusion, Maltese (a derivative of Arabic with an admixture of Italian) used to be a little-known language outside its native island, but its profile and that of its translators rose overnight when Malta joined the European Union in 2002 and thus Maltese became one of the Union's official languages with rights of use in Brussels, Strasbouurg etc. However, the sudden elevation caught the country unprepared and complaints followed. It's led to situations like the following:

"When Magistrate Aaron Bugeja entered the court room, lawyer Giannella de Marco, who together with Steve Tonna Lowell was representing Mr Bailey [the Englishman who was accused] asked for the identity of the interpreters.That was in 2016. Here's the latest, from the Times of Malta.

The court provided Dr de Marco with a list of practicing lawyers and a woman who was qualified in French rather than English.

After consulting her client, Dr de Marco requested a professional simultaneous interpreter who would be qualified as an interpreter in Maltese and English and insisted this was important in the interest of justice.

Magistrate Bugeja pointed out that while Dr de Marco had a right to this request, it would prolong proceedings. The case was put off to a later date."

"What is wrong with the training of the so-called qualified translators in Malta? What is wrong with the training of the so-called qualified [i.e. professional] translators in Malta?… Why is it that incompetence reigns supreme in Malta, especially when it comes to official documents? Why can they not train people properly? How dare people even translate from or into languages they do not understand correctly and do not master?"This seems to reflect badly on the country's principal training institution, which is the Department of Translation at the University of Malta. But the Department blames the authorities.

"The lack of a warrant [i,e, accreditation] system for professional translators and interpreters meant unqualified individuals could produce sub-par work for use in official documents and court cases, staff and students at the University's Department of Translation have warned.The situation isn't likely to improve in the near future. EU member states have until August 2018 to compile a list of professionals certified to translate public documents. "There has as yet been no attempt to compile such a list,"

In a statement decrying the existing unregulated state of affairs, members of the Department of Translation, Terminology & Interpreting Studies called for Malta to introduce an accreditation system for trained translators. It is unacceptable that one of the highest institutions in Malta, and a pillar of our democracy, is resorting to people who are not qualified to act as interpreters and translators," they said."

There are many other places where the situation is no better. Our point is not that Malta is particularly bad but that translatologists seeking accuracy in their research must beware of equating professional translator with expert translator.

Historical footnote

When Napoleon's fleet sailed fro Toulon in the summer of 1798 on his ill-fated but scientifically enriching expedition to Egypt, he made a stopover of a week on Malta. He foresaw that he would need to promulgate his proclamations to the Egyptians in Arabic.

"He brought hs own translators and interpreters with him, including some Muslim sailors whom he had captured in Malta. These 'foreign' translators prepared the Arabic circular that Napoleon distributed on landing in Alexandria, a circular designed to reassure the Egyptian populace and to incite them to rebel against their rulers. The circular, like much of what these foreign translators produced, was grammatically unsound and stylistically poor." (Mona Baker citing al-Jabarti, the leading Egyptian chronicler of the period)As a result it was met with derision.

Sources

Call for professional interpreter delays Papaqli case hearing: lawyer argues that client had right to professional interpreter. Times of Malta, 28 October 2'16,

Marie Paule Wagner. Incompetent translators. Times of Malta, 15 February 2018.

Mona Baker. Arabic tradition. In M. Baker et al.(eds.) Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies. Routledge, 1998, p.322, for the Napoleonic episode.

Image

University of Malta in Maltese.

Friday, February 9, 2018

Young Translators Champions 2017-2018

The European Commission has just announced the winners of its latest Juvenes Translatores (Latin for Young Translators) competition. This is an annual contest that it runs for 17-year-old secondary school students across the European Union. This year's winners, all 28 of them (one from each member state), will go to Brussels on 10 April to receive their trophies and diplomas. There's no overall winner; it would be too difficult to judge one, especially as there are considerable differences between the styles of the various texts.

The competition has been building up for some years since it was launched in 2007, and consequently there's already quite a full commentary on it spread over several posts of this blog. I won't repeat it all here because you can retrieve the series just by entering juvenes in the Search This Blog box on the right. But here are a few reflections on this year's results,

Some figures. There were over 3,300 contestants, up from about 2,000 in 2010. This indicates that enthusiasm for translation as a competitive skill has by no means waned. It illustrates that translating can be done for pleasure, as a hobby, as a game; as what we called ludic translation in 1987 when done by young children. It can be a mind-tickling game like crosswords or Scrabble.

In view of the constant (and justified) complaints in the United Kingdom about the decline of language teaching in the schools, it's particularly encouraging to see the large number of contestants from there (312 from 73 schools), surpassed only by Germany (370), Italy (352) and France (333).

There's no doubt that one of the reasons for the large number of UK contestants is the continued tradition of language teaching in the grammar schools (see Term below), a tradition that includes translation exercises – the kind of syllabus I went through myself. There are no fewer than 13 such schools in the list of participating schools. The UK winner was Daniel Farley from Manchester Grammar School for a Spanish to English translation. His school was founded in 1515 by the Bishop of Exeter to provide "godliness and good learning"' to poor boys in the city of Manchester.

The winning entries are available on the first EC website listed below; and so also – if you would like to try your hand at one of them – are the source texts.

Grading 3,300 translations is no mean job. The staff of the EC who were involved should be thanked warmly for their dedication

Sources

European Commission. Juvenes Translatores 2017 Contest. https://ec.europa.eu/info/education/skills-and-qualifications/develop-your-skills/language-skills/juvenes-translatores/2017-contest_en, or click [here].

European Commission. Juvenes Translatores: announcing this year's winners of the of the European Commission's translation contest for secondary school students. Press release, 2 February 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/info/education/skills-and-qualifications/develop-your-skills/language-skills/juvenes-translatores/2017-contest_en or click [here].

Term

Grammar school. A UK secondary school of a type with Renaissance origins that stresses academic rather than a practical or vocational education. There are over 100 of them. They got grammar in their name because they taught the grammar of Latin and other languages. Nowadays they've become controversial because of their selective admission. My father went to the King Edward VI Grammar School in Birmingham, where he won a prize for German in the form of a beautifully bound anthology of German poetry.

Monday, January 29, 2018

Inspirational and Inspired Interpreting

We kick off 2018 on this blog with a post about church interpreting, a function which is mostly performed by non-professionals. It has been an unusually long time since the previous post, and for this the pandemic of flu of the long-lasting, misnamed 'Aussie flu' variety is mainly to blame. My apologies for not wishing all you Followers a Happy New Year.

The conventional image of the ideal interpreter is that of a neutral, colourless transmitter of information who neither adds to nor subtracts from nor influences the message. This is what is taught in the training schools due to the long tradition of professional interpreters themselves conducting training and research, and no doubt it fits a great many interpreter functions such as court interpreting, most conference interpreting and community interpreting. Nevertheless there are important areas that it doesn't describe, or at any rate not adequately.