A few posts ago (February 20), there was one on this blog about Translators in Schools. British schools, that is. Now here's some information about a related UK initiative called Translation Nation. Actually it's the elder of the two, though it's slipped under my radar until now.

"Translation Nation is an award-winning project which aims to inspire children and young people to begin or continue what we hope is a lifelong exploration of literature and culture from around the world. The project promotes pride and enthusiasm for the many languages that are spoken or taught in UK schools, encourages recognition for the important role translation plays in our lives, and encourages an enjoyment and appreciation of literary English and the nuances of the English language."The project is a partnership between Eastside Educational Trust and the Stephen Spender Trust. (Though the name sounds American, Eastside refers here to the East End of London.) It was started in 2010 for primary schools and in 2012 it received both the European Language Label and the EuroTalk Primary Education Language Prize. The project was also re-launched that year to extend its work to primary schools.

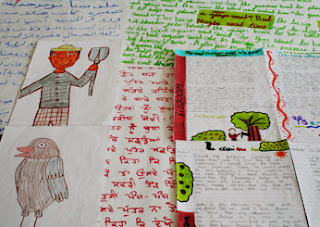

"Translation Nation empowers primary school children as translators, interpreters and storytellers of international stories. It celebrates the many community languages spoken by the children and encourages a curiosity about world literature. Working in small groups under the guidance of language experts, the children translate into English and re-interpret stories that their parents have shared with them from their home languages. The process introduces the children to literary fiction and by including music, props and performance the children find it easy to become engaged and the workshops encourage a more thoughtful, confident, nuanced and imaginative approach to writing in EnglishThese initiatives are – or should be – important to translatologists because they extend significantly the scope of translating by children and adolescents. In recent years, most of the research attention in this area, and especially in the USA, has been focused on child language brokering (CLB), which means basically the translating that individual bilingual children of immigrant families do in order to help out other, less bilingual members of their families and immediate entourages. This has expanded, mainly in the UK, to organised LB teams in schools, and even to a whole movement like the East Hampshire Young Interpreters (enter hampshire in the Search box on the right). It does reinforce our certainty that normal children without special gifts or teaching can translate, but it has a serious limitation. Which is that CLB is only done for utilitarian purposes and to maintain personal relations with its beneficiaries.

"Translation Nation in secondary schools creatively and persuasively highlights to students the value of multi-lingualism today and the opportunities it brings in social and professional contexts and in accessing global literature and culture. The project enables pupils through a single workshop to build confidence as translators and to see the relevance of the modern foreign languages (MFLs) they learn in school. It promotes the continuation of MFL learning to equip pupils with highly desirable tools for the future."

Now comes a quite different kind of stimulus and a quite different kind of adult intervention. The interveners aren't school teachers but are themselves translators or "language experts". And their aim is not utilitarian but to help children's cultural development. This goes along with the general observation that although most translating may be performed to facilitate practical communication, there is nevertheless a great deal which is not (starting with the ludic translating done by the very young like Leopold's daughter.) Activities such as TN point the way to how children's natural translating ability can be developed in pleasure-giving non-utilitarian areas too.

References

Eastside Educational Trust. Translation Nation: inspiring literature in translation in schools. Click here.

Werner F. Leopold. Speech Development of a Bilingual Child: A Linguist’s Record. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1939-1949. Reprinted New York: AMS, 1970.

Image

Source: www.eastside.org.uk